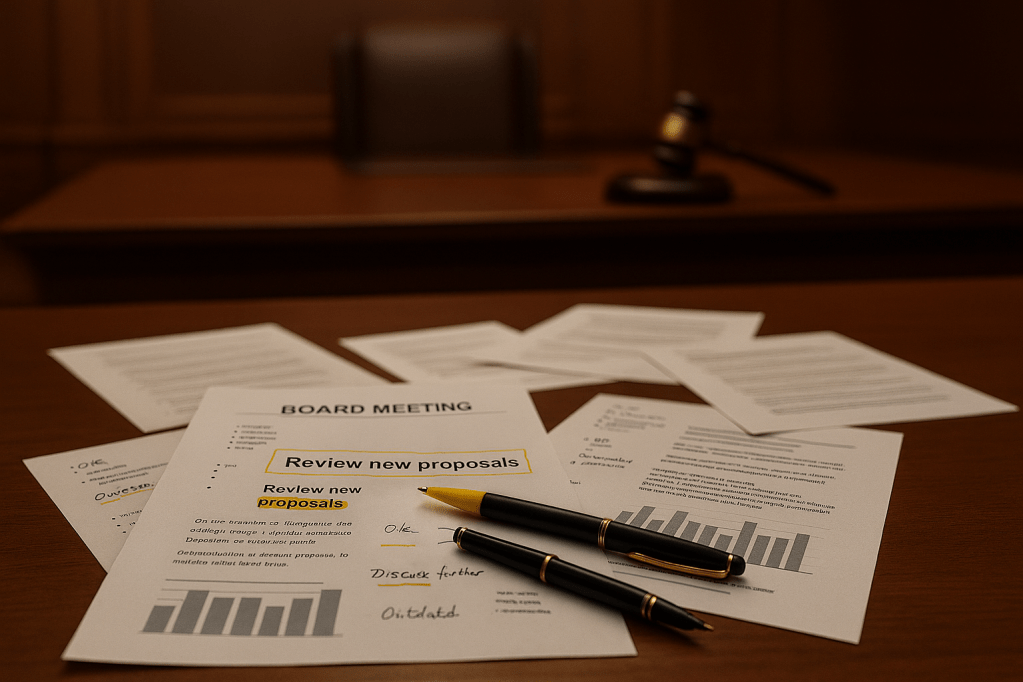

Directors pride themselves on diligence – reading board papers thoroughly, making notes, and preparing for robust discussion. But the governance world continues to operate under increasing scrutiny, where every decision and document could potentially become evidence in future disputes. Annotations on board papers, while useful for personal clarity, introduce complexities that boards and directors should understand. They are not simply private notes; in the context of litigation, they can become part of the evidentiary record and may be interpreted in ways that were never intended.

It’s natural to think that jotting down reminders or highlighting key points is benign. Annotations often feel like a practical tool for engagement; but in litigation, they can attract attention beyond their intended purpose. As former Chair of ASIC Alan Cameron noted in an AICD magazine in November 2012:

The risk is not with the annotations you have made, but with the annotations you didn’t make. If you make all these worthwhile annotations, you are still likely to be cross-examined about why you thought X was worth mentioning and why you didn’t mark Y and so on. And, if you say you did discuss Y, but it is not marked electronically or on the papers, you are likely to be disbelieved.

This observation highlights a key issue: selective annotation can prompt questions about a director’s judgment and priorities. If one issue is highlighted and another ignored, courts may interpret omissions as significant, even if they were benign at the time. It could also be “a red flag in hindsight or future discovery proceedings if you take copious notes in some meetings and none in others”.

This issue of annotating board papers was discussed extensively in 2018 in an American context by Katz and McIntosh in the New York Law Journal. They note that:

Many corporate secretaries, as well as outside counsel, discourage any note-taking by directors to minimize the possibility that these notes could create issues at some future time. Directors are often counseled that the length of their deposition in any shareholder litigation will have a direct correlation to the amount of notes they have taken and retained.

Under Australian law, personal notes and annotated board papers are generally discoverable and, even if intended only for personal clarity, may end up being examined in court. For example in Brady v NULIS Nominees (Australia) [2024] FCA 1374, Markovic J made use of handwritten notes taken by an executive at board meetings and board workshops (e.g. at [206] and elsewhere); and in the Centro case, where Middleton J observed (at [327]) that the company secretary took handwritten notes during a meeting of Centro’s Board Audit and Risk Management Committee:

She was a very diligent note taker, and her notes are comprehensive and detailed. It is apparent from her notes that the following relevant events occurred at this meeting.

Courts are clearly prepared to rely on contemporaneous notes to reconstruct events, which underscores the evidentiary weight of board paper annotations.

The Governance Institute of Australia’s “Board papers” guidance proposes that each board form their own view on the circumstances in which directors and others will be permitted to retain papers beyond the meeting to which they relate, explicitly noting directors’ duties, rights of access to board papers, and the need to mitigate risks associated with annotated papers. It frames retention (and the treatment of annotations) as a governance design question: boards should deliberately determine who keeps what, for how long, under what controls, and with what privilege measures, rather than leaving retention practices to informal habits. The AICD echoes this guidance, recommending that that companies adopt and consistently apply an appropriate document management and retention policy generally, and that the policy explicitly address when drafts and handwritten notes are required to be retained and when they may be destroyed.

Before any board meeting, directors should thus understand and consider their organisation’s policy on board paper retention and consider whether annotations could be interpreted beyond their intended purpose. During the meeting, they should engage actively with the discussion and ensure clarity in the official record, marking any notes related to legal advice appropriately (in case they could be considered legally privileged). After the meeting, directors should review how personal notes align with governance protocols and confirm that minutes accurately reflect decisions and rationale. (Note that these steps do not prescribe a single approach, but rather illustrate the considerations that can help directors navigate this complex area.)

Annotations can be helpful for preparation, but they also introduce interpretive and evidentiary complexities. They can create asymmetrical risk because they often lack context and can be interpreted in ways that were never intended. Notes will naturally lack any full discussion narrative, which means a brief comment can be misinterpreted, and differences between notes and minutes can raise questions about accuracy and consistency. Courts, regulators, and litigants may examine them closely, sometimes years after the fact. Understanding these dynamics – and aligning practice with governance guidance – can help directors navigate the balance between convenience and risk. Ultimately, the question is not whether annotations are good or bad, but how they fit within a broader governance framework that protects both the organisation and its directors.